Will labor migration cause the speeding up of social security reforms?

The hot debate on opening up of labor markets of “old” EU states has much more angles than in traditionally perceived. Feared by the West and most desired by the East, it seems to be of important magnitude: in the UK, there are 350 thousand legal workers from the NMS, ( Commission Report ) of which most relatively young (80% under the age of 34, 44% under the age of 24), with another 100 thousand in Ireland.

This migration, seen sometimes as a solution to many of the CEECs economic woes, is often being implicitly encouraged as contributing to the reduction of unemployment. But it may just turn out that it will create more troubles than it will bring gains – unless crucial reforms are sped up in Central and Eastern Europe.

The picture is not as beautiful as often painted – there are quite a few arguments that should lead analysts to give a closer look at the structure of this migration.

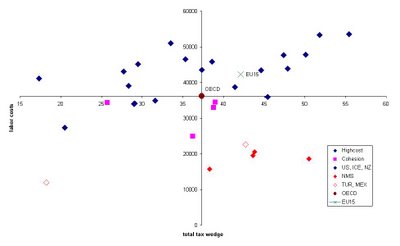

First of all, it is important who leaves. As most of the CEECs have at least partial pay-as-you-go retirement schemes, the question whether the people that do leave would be able to get a job at home may be quite important. If it is an unemployed, who receives benefit and has little prospect of finding a job at home that goes this should reduce the burden on the ones that stay. But if it is young people, people working, or potentially able to find a job in the near future that leave – this may at a point pose a threat to the sustainability of the social security systems and especially pension schemes. The outflow of (potential contributors) reduces the revenue of social security schemes – at the same time leading to an increase in the burden on the workers that remain in the country. And this burden is already relatively high, compared to total labor costs (see Figure 1).

Second, it matters in what character these people go – if the migration is temporary, but workers come back to set up there own businesses once they gather some capital – this may eventually reduce the pressures. But if they stay abroad, they will contribute to the pension schemes in there new home countries instead of the NMS, while even without taking this migration into account dependency ratios in CEECs are expected to increase substantially in the next years. Thus the burden on the ones that remain should increase even further.

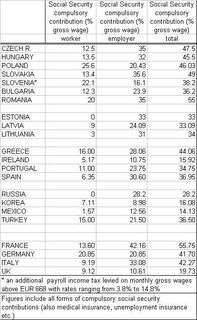

In Table 1 we have the average income workers’ social security burdens. The figures, especially for the larger CEECs, are comparable to the highest EU numbers, while being relatively high compared to other emerging market countries and even the ‘cohesion’ group of EU members (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain). In the former comparison, demographics may be claimed to help explain some of the difference, the demographic structure and forecasts for CEECs and cohesion states are not much different.

Figure 1: Tax wedge and total labor costs (source: OECD). New Member States (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) in red, Cohesion States in pink, developed countries in dark blue.

Table 1: Compulsory social security contributions as % of gross salary.The data is for 2005, in percentage of gross salary of a person earning 100% of the average wage. The figures are not directly comparable, as include country specific taxes, but are useful to give a picture of the burden that is borne by average workers. Source: World Bank, National Ministries' websites, www.worldwide-tax.com, Social Security Agency, OECD.

Thus if it is not (just) the demographics, then quite probably the inefficient social security systems have a strong say – fifteen years after the start of transition, despite various reform attempts, most countries have still an over-blown, and relatively costly system, inherited from the previous regime and difficult to reform because of strong interests groups.

Economists do not provide much of an argument that PAYG systems should be inferior to savings systems, and in fact with some conditions fulfilled these can be equivalent. And despite most schemes are at least intended to be self-financing it is usually up to the government to finance any deficits – but this is just another cost a taxpayer must bear.

As said, reforms are being introduced, though usually at a gradual pace, but this may prove just too slow. They include raising the retirement age, especially for women, switching away from the PAYG to two or three pillar schemes and reducing possibilities of early retirement. Yet strong groups of interests together with political populism often impede more ambitious attempts – just for example in Poland – some of the reform plans were watered down due to protests of interest groups (miners, which were given special concessions) before the last elections.

Therefore, with ‘unfavorable’ demographics and still inefficient social security systems it may just be that workers migration to the old-EU will inevitably force the reforms to speed up.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home