Hungary's new tax rises - a comment

An article in todays FT (18/07/06, Hungary’s new tax rises go against the east European trend” by Christopher Condon) raises preoccupation about the proposed tax increases citing various voices that it have a negative effect on FDI inflows.

However, if we look at the situation closer – a serious decrease in FDI because of the recent rise in corporate profit tax from 16% to 20% seems rather doubtful.

First of all at 20% the corporate tax rate will remain relatively low, even in the region, comparable to neighboring Slovakia’s 19% (where there are talks of changing taxes, rather upwards), Czech Republic’s 24%, Austria’s and Slovenia’s 25% , though admittedly above the rates in Romania(16% after decrease in 2005) and Bulgaria (15%) . Thus the upward change, albeit against a trend in the region, will not make Hungary stand out among its’ neighbors.

Second, many FDI target projects, especially greenfield projects are accompanied with state-aid or tax incentives therefore the pure increase in corporate tax rate may have little actual effect on the firms’ decision where to locate its’ investment. Issues like good infrastructure and good business environment, which Hungary seems to have to a larger extent than Bulgaria and Romania (for instance, World Bank Doing Business in 2006 classifies Hungary as 52nd, while Bulgaria ranks 62nd and Romania 78th while this does not take into account crime and corruption figures) tend to be important as well.

Last, but most importantly – we must remember the context in which we judge the increase in taxes. If we take as a counterfactual Hungary without a tax increase and omit the huge double deficits the country faces – we will not be making the proper comparison. Regardless of the corporate tax rate, no country in the region has a fiscal position as negative as Hungary – and if it were to remain (or deteriorate) it would most certainly bring about a crisis, for which it is quite doubtful we would see no negative effect on FDI.

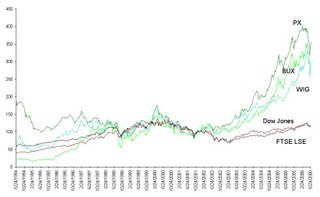

With a fiscal deficit as per cent o GDP of nearly two digits, the situation in Hungary is looked upon with attention not only by policy makers, but also by foreign investors.

As companies care for a risk weighted return (or rather flow of expected returns) a looming crisis would certainly affect their decision whether to invest in a country or not. And failing to consolidate the fiscal gap in Hungary would bring effective risks to the country (we talked about it on the TEblog here… and here... ) especially as the current situation is not only alerting but also unsustainable. Improvement of Hungary’s fiscal position would reduce the risk of crisis, and improve (or rather make realistic at all) the prospects of joining the Euro. While, an increasing prospect of the crash of the forint is certainly be an important scarecrow for foreign investors.

So can we realistically assume a corporate tax change of a couple of percentage points would be more harmful for the inflow of investment then the luring crisis, which would most probably hit if the gap between public spending and revenue was to remain? I don’t think so. And in this I do not want to say that the tax reforms will suffice to maneuver the Hungarians out of a difficult fiscal situation. A more decisive stance on the spending side of public finance would be welcome in order to achieve sustainability, but the attempts to increase corporate (among other) taxes, should have little if any negative effect on FDI.